Fitness Is Not Therapy, But It Helps Me Shut Up

The gym is not therapy.

It won’t unpack your childhood, heal your attachment issues, or solve the mess in your journal.

But I won’t lie — lifting heavy things, running long distances, and sweating buckets?

That stuff helps me SHUT UP.

Not literally. I mean the voice in my head that’s always overthinking, catastrophizing, spiraling.

Anxiety Is Loud. Movement Is Louder

If you’re like me — a chronic overthinker with 32 browser tabs open in your brain at all times — you know what it feels like when your thoughts won’t sit still. But here’s the wild part: neither will your brain.

According to neuroscience research, your brain has a “default mode network” (DMN) (Gillespie et al., 2020). It’s the network that lights up when you’re not doing anything.

Basically, the background noise that plays when you’re zoning out, daydreaming, or overanalyzing that one text.

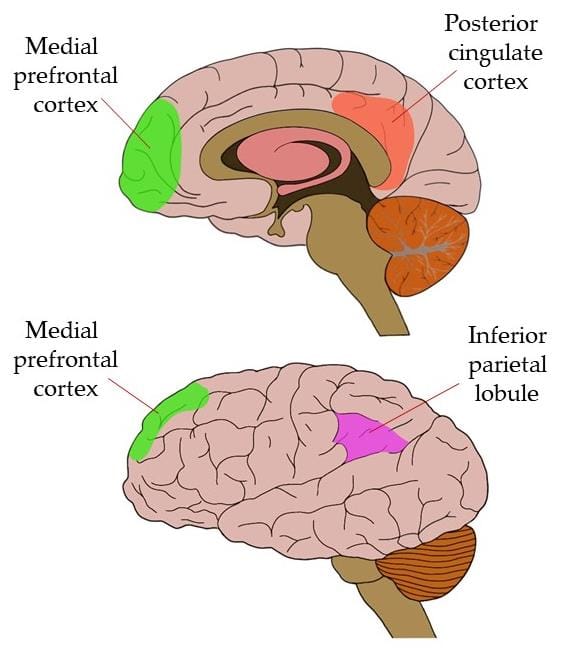

The image below show a group of brain regions that become most active when your mind is at rest (not focused on a specific task). It’s the part of your brain that lights up when you’re:

- Daydreaming

- Thinking about yourself

- Replaying past events

- Worrying about the future

- Overthinking (hi, relatable)

Key Brain Areas in the DMN:

- Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC) – Green area

- Involved in self-reflection and thinking about your emotions or what others think of you.

- Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC) – Red-orange area (top image)

- Linked to memory, self-awareness, and imagining the future or past.

- Inferior Parietal Lobule (IPL) – Purple area (bottom image)

- Helps you understand social situations, others’ thoughts, and where you are in time and space.

When you’re inactive — like lying down, zoning out, or endlessly scrolling — the DMN becomes highly active. This can lead to mental patterns like rumination, worry, and anxiety, especially for overthinkers.

But here’s the science-backed upside: exercise and focused movement have been shown to reduce DMN activity (Garrison et al., 2015). In simple terms, moving your body gives your brain a break from its constant background noise.

This is why physical activity often helps calm racing thoughts, not because it’s a substitute for therapy, but because it shifts your brain into a more present, task-oriented state.

Endorphins, But Make It Science

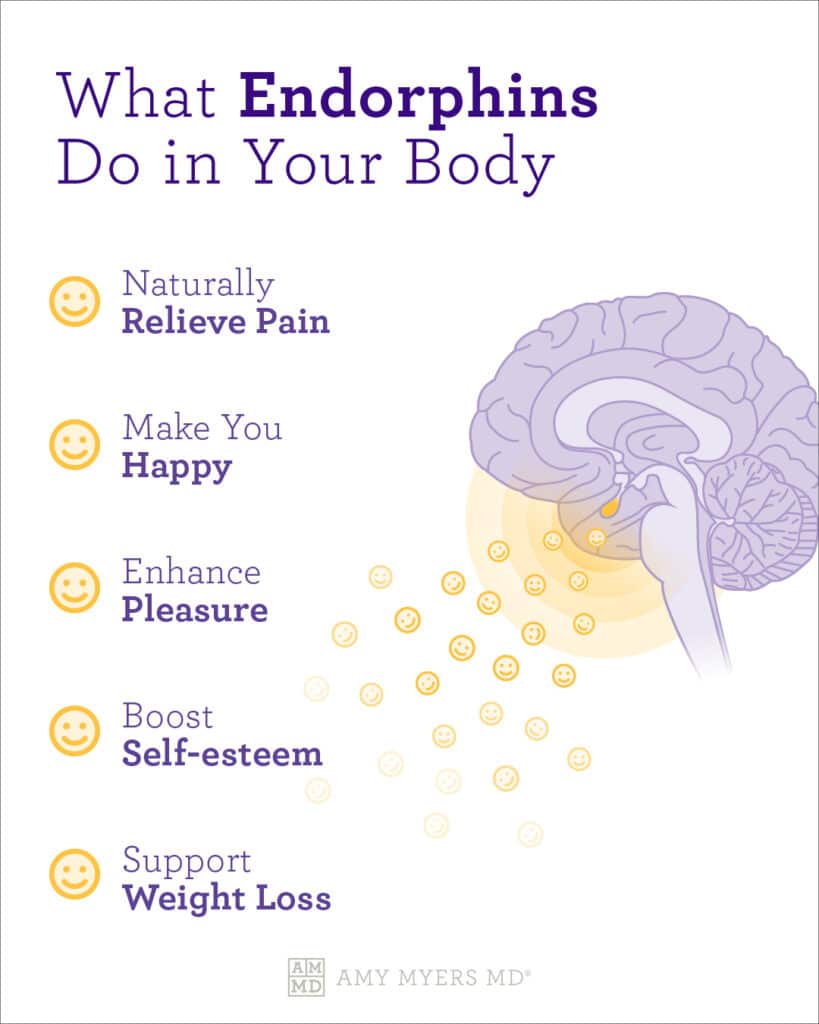

We always hear that “exercise releases endorphins” — but for the longest time, that just sounded like fitness bro talk to me. It wasn’t until I actually stuck to a workout routine that I realized: it’s chemistry (NERD!).

When I started lifting and running regularly, something shifted. Not instantly, but gradually. I wasn’t magically cured of overthinking or suddenly free from stress.

But I noticed that after a solid gym session or a long hike, the noise in my head? It got quieter.

Science backs this up:

- Exercise increases endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers and mood boosters (Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

- It also boosts dopamine and serotonin, which help with motivation, focus, and keeping your emotions in check (Watson, 2024).

- And even cooler? It raises levels of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), which literally helps your brain adapt and grow and has been shown to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (Sleiman et al., 2016).

So no, working out doesn’t magically fix my internal monologue about not being good enough or my fear of failure. But it gives me space.

And on some days, that space is the only thing between “I can’t do this” and “Let me try anyway.”

When My Mind’s a Mess, My Muscles Step In

There are days I show up to the gym not because I feel strong — but because I feel scattered. My head’s spinning with unfinished to-do lists, overanalyzed conversations, and the classic “What am I even doing with my life?” crisis. I don’t feel motivated. I feel mentally messy.

This happens frequently! At first, I thought it is not normal.

But then I start moving.

I pick up a barbell. I focus on my breath. I check my form. My mind — which five minutes ago was spiraling — starts doing just one thing: counting reps. Not regrets. Not worries. Just reps.

And it’s weirdly peaceful. Not happy, not fixed — just quiet.

The gym doesn’t erase my problems. It doesn’t make my life magically less overwhelming. But it gives me a moment where my thoughts aren’t fighting for attention where my body takes over and tells my brain: “You can rest now, I got this.

And most days, that moment of silence is enough to reset. Enough to remind me I can keep going, even if everything’s not together yet.

Fitness ≠ Cure

Let’s not get it twisted:

- Exercise is not a substitute for therapy.

- It’s not a fix for trauma, ADHD, or clinical depression.

- And no, you can’t “run away” from emotional wounds (though I have tried to outrun overthinking — one 10K jog at a time).

But what it can do is give you a healthier baseline. A sense of stability. Momentum. It helps regulate your nervous system, improves your sleep, reduces stress hormones like cortisol, and makes you feel just a little bit more capable of taking on life.

TL;DR: It’s Not Deep. But It’s Deep.

So no — fitness isn’t therapy.

But when my brain is being stupid, my body knows what to do.

When I can’t make sense of anything, I lift. I run. I move. Not to solve the problem, but to silence the noise long enough so I can breathe.

References:

Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Endorphins: What They Are and How to Boost Them. Cleveland Clinic; Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23040-endorphins

Garrison, K. A., Zeffiro, T. A., Scheinost, D., Constable, R. T., & Brewer, J. A. (2015). Meditation leads to reduced default mode network activity beyond an active task. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 15(3), 712–720. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-015-0358-3

Gillespie, C. F., Szabo, S. T., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2020). Unipolar depression. Rosenberg’s Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disease, 2, 613–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-813866-3.00036-9

Sleiman, S. F., Henry, J., Al-Haddad, R., El Hayek, L., Abou Haidar, E., Stringer, T., Ulja, D., Karuppagounder, S. S., Holson, E. B., Ratan, R. R., Ninan, I., & Chao, M. V. (2016). Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate. ELife, 5(e15092). https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.15092

Watson, S. (2024, April 18). Feel-good hormones: How They Affect Your mind, Mood and Body. Harvard Health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/feel-good-hormones-how-they-affect-your-mind-mood-and-body

Member discussion