My Time Management is a Lie (But It Works?)

Welcome to my first post! :))

Let me be honest: I look like I have my life together. My calendar is color-coded. My to-do lists are segmented by priority levels. I even have a Google Sheet titled “Admin System for __ Semester”.

But if you’ve ever texted me and I replied three days later with “Sorry, super hectic week,” just know: I wasn’t lying — I was probably deep in a productivity spiral about being productive.

Here’s the thing: I’m not naturally organized. I just panic-plan a lot.

The Illusion of Discipline

Some of my colleagues assume I’m good at time management because I lift regularly, keep up with academics, and still make time for hiking or journaling.

But truthfully?

Most of my routines weren’t built from discipline. They were built from desperation. From the need to not fall apart and to be in control. From survival mode. From realizing that if I didn’t map out my time, I’d be drowning in it.

I’ve literally scheduled everything. I time-block my naps. I set alarms not just to wake up, but to remind myself: “hey, stop pretending to be busy — it’s time to actually be productive.”

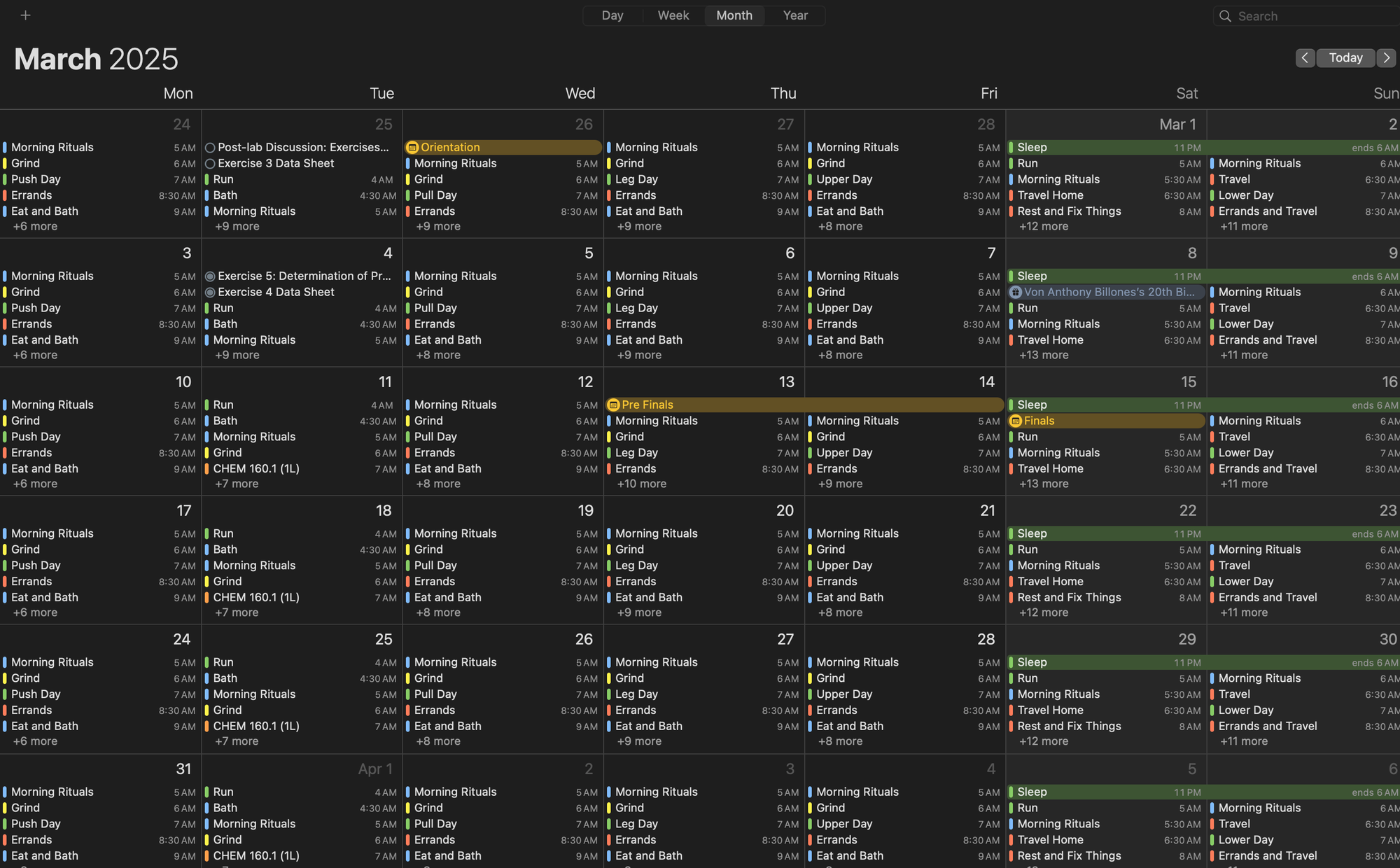

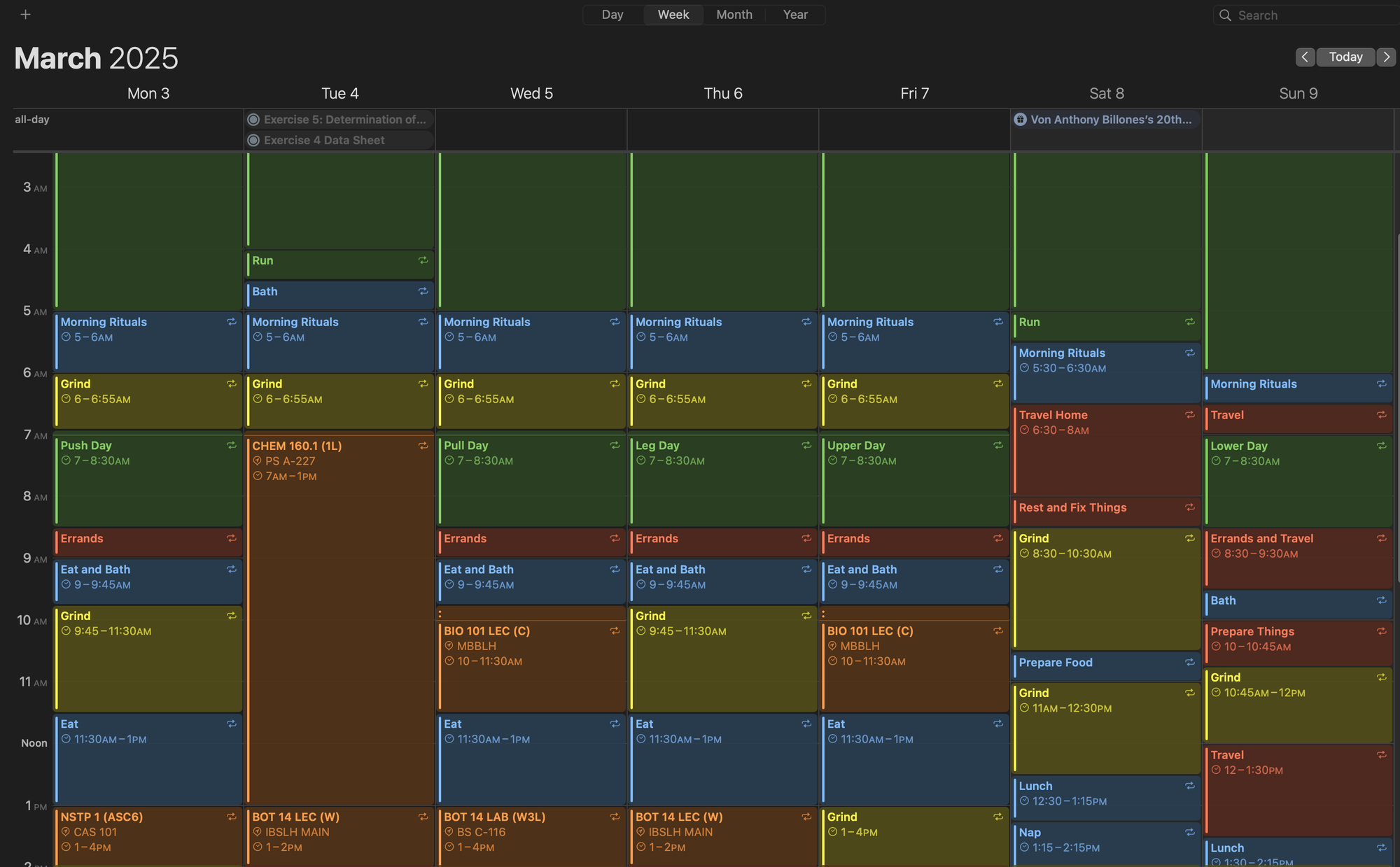

And this is what my calendar looked like during my second year in college.

It looks overwhelming, right? Like something only a control freak or a robot would create. But zoom in:

It starts to make sense. You realize it’s not rigid — it’s a coping mechanism. It’s not about over-efficiency. It’s about regulating chaos in small, bite-sized blocks.

According to cognitive psychologist John Sweller, our working memory (aka the part of our brain that handles immediate tasks) can only hold a small amount of information at any one time (Williams, 2022).

That’s it. That’s why when your day feels like a cloud of tasks, your brain goes into panic mode.

Breaking things down, especially visually through a calendar or time blocks, is a way of reducing cognitive load. It actually frees up mental space so you can think more clearly.

There’s also a term in productivity psychology called “implementation intention” a concept introduced by Dr. Peter Gollwitzer. It basically means you’re more likely to do a task if you pre-decide when and where you’ll do it (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006).

So blocking out your day with specifics like “Study BIO 101: 4:00–5:30 PM” instead of “Study sometime today” gives your brain clear instructions.

Clear = Doable

So yes, it might look smooth and structured from the outside. But behind the scenes? It’s chaos disguised in not-so-aesthetic Apple Calendar boxes.

It’s a system that was born not from perfection, but from panic, trial and error, and the need to feel like I had a handle on something.

But it works.

Not because I’m naturally disciplined, but because I built a system that keeps me from falling apart when motivation disappears.

Organized Mess > Unstructured Stress

I’m not saying my system is perfect. I still miscalculate how long tasks will take. I’ll plan a “light day” and somehow end up editing a paper, lifting, doing org work, and meal prepping all before 10 PM.

There are days when I reschedule half my calendar not because I’m lazy, but because my brain and body just aren’t on board.

But here’s the thing: I don’t cram. I hate that feeling of racing against a deadline. That’s why I plan even when I know I won’t follow it 100%. Because even when I’m off-track, I’m still better off than if I hadn’t planned at all.

This approach is not my coping mechanism — it’s actually backed by science (researched it, you know!)

Psychologist Roy Baumeister, known for his work on willpower and decision fatigue, found that people with high self-control don’t necessarily have more discipline, they just design lives that require less of it (American Psychological Association, 2012).

In other words, the secret to discipline isn’t grinding harder. It’s pre-deciding what matters and protecting your mental energy.

This is what a sample day looked like last semester. As you can see, every time slot had a specific block, I didn’t leave anything blank. There had to be something I needed to accomplish during that time.

I barely had any rest in between, but I considered gym sessions and eating while watching my favorite series as my breaks.

That’s what my time blocks do. Even when they’re reshuffled or imperfect, they reduce the mental load of constantly asking “What now?” They give structure to the chaos, even if I only follow 60-80% of the plan.

And according to behavioral economist Dan Ariely, we’re terrible at predicting how we’ll feel or perform in the future (Ariely, 2010). So I build buffers into my schedule — not because I’m weak, but because I know I’m human.

Some days I’m mentally on fire; other days, I’m dragging myself through flashcards with half a brain cell. My system works with that variability, not against it.

Why It Still Works (Kind Of)

For me, time management isn’t about optimizing every minute or chasing some hyper-productive ideal. It’s about managing energy, setting realistic expectations, and building in recovery.

I don’t schedule things to control every part of my life. I schedule them to create space in my life.

When I break my day down into blocks, it helps me keep the momentum going, even on days when motivation disappears. And when things don’t go as planned (because they rarely do), having a framework helps me pivot instead of panic.

Also, I’ll admit: I like the illusion of control. Color-coding my calendar or making a checklist is not all about aesthetics — it’s a grounding tool.

Research shows that visual structure reduces anxiety, especially for people balancing a lot of moving parts (Robinson et al., 2013). And between my academics, gym goals, social life, org responsibilities, and mental health? I need all the grounding I can get.

Especially when I’m studying CHEM 160.1 (Introduction to Biochemistry Laboratory) one hour and meal prepping the next, trying to keep both my GWA and protein intake alive 😭.

So yeah — my time management might look clean on paper, but the reality is a flexible, evolving system held together by intentional effort, not perfection.

And the good news is: it works (kind of). Not because I’m always on track, but because I’ve learned to give myself grace when I’m not.

And honestly? That’s more sustainable than any planner hack out there.

The Takeaway?

If your time management system is built on vibes, half-lies, panic plans, and semi-functioning routines, I guess welcome to the club. You’re not failing. You’re adapting.

PS: If you also write “study” in your planner but end up watching Modern Family (my favorite TV show of all time) reruns because you “needed comfort,” I see you. You’re valid. We’ll try again tomorrow — probably??

References:

American Psychological Association. (2012). What you need to know about willpower: The psychological science of self-control. Apa.org. https://www.apa.org/topics/personality/willpower

Ariely, D. (2010, March 25). The Long-Term Effects of Short-Term Emotions - Dan Ariely. Dan Ariely; The Long-Term Effects of Short-Term Emotions. https://danariely.com/the-long-term-effects-of-short-term-emotions/

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta‐analysis of Effects and Processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38(1), 69–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

Robinson, O. J., Vytal, K., Cornwell, B. R., & Grillon, C. (2013). The impact of anxiety upon cognition: Perspectives from human threat of shock studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7(203). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00203

Williams, D. (2022). The importance of cognitive load theory | Society for Education and Training. Society for Education & Training. https://set.et-foundation.co.uk/resources/the-importance-of-cognitive-load-theory

Member discussion