Rest Days Are Emotional for Me (and That’s Okay)

I was supposed to be studying right now, enlisted in a summer course (PI 10: Life and Works of Rizal) and being “productive.” But thanks to a broken system and some real registration chaos, I didn’t get in. So now I’m on an unplanned vacation I didn’t ask for.

And yeah, I know rest is important. I preach it to friends, repost quotes about burnout, even tell myself I deserve to breathe. But now that I actually have space — no coursework, no deadlines, no calendar alerts, I feel this low-level panic.

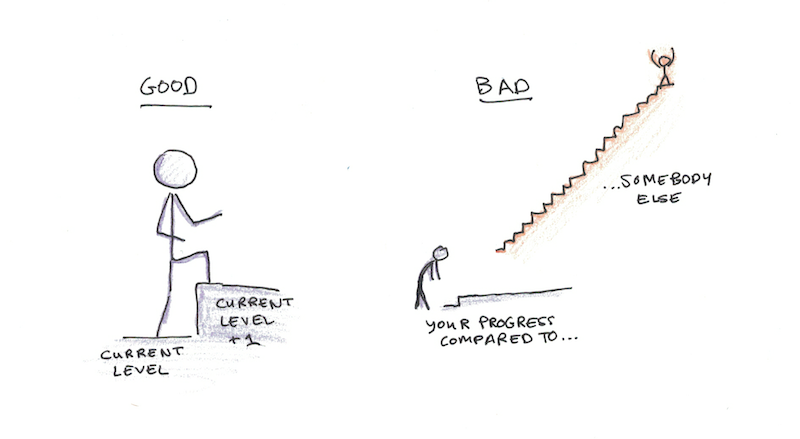

Like I’m falling behind in a race that no one else seems to be running. I scroll through my phone trying to enjoy the downtime, but that guilt creeps in like clockwork: “Shouldn’t I be doing something?”

Still, here’s what I’ve realized: rest is NOT a glitch in the plan. It is the PLAN. It just doesn’t always feel easy.

Sometimes it’s heavy.

Sometimes it’s frustrating.

Sometimes it feels unfair.

But maybe that’s not a sign of failure. Maybe it’s proof that I’m in the middle of unlearning. And that’s work, too.

The Productivity Trap

We live in a world that romanticizes exhaustion. Hustle culture glorifies 16-hour workdays, all-nighters, and “no days off” as badges of honor. Rest, on the other hand? It’s often treated like a luxury — or worse, a weakness.

It is neurological. According to self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), we’re wired to seek autonomy, competence, and relatedness but when competence gets hijacked by constant output, we start measuring our worth by how much we do.

In fact, a 1999 study by Onwuegbuzie & Daley found that people with a high “need for achievement” tend to experience more guilt when taking breaks even if rest improves their performance. This guilt is so common it has a name: “productivity guilt” (Young, 2018).

Even the act of resting can become performative. Ever found yourself reading a self-help book on your “rest day” just to feel like you’re still improving yourself? Yep.

That’s the trap.

The Mental Spiral of Rest Days

Here’s what my inner monologue sounds like on a typical rest day:

“You should probably get ahead on something.”

“Other people are grinding right now, and you’re lying here?”

“At least do a light workout. Or clean something. Or read a ‘smart’ book.”

It’s not that I don’t want to rest — it’s that I feel like I have to earn it.

Psychologist Emma Seppälä, author of The Happiness Track, explains that rest is a core component of emotional regulation and resilience.

When we deny ourselves rest, we’re more likely to experience stress, emotional fatigue, and cognitive decline.

And yet, rest triggers all these deeply conditioned fears: of laziness, of failure, of not being “enough.” This spirals into what researchers call “achievement-based identity” where your sense of self is tethered to productivity (Huynh, 2022).

Sometimes, I try to “half-rest” — you know, watching Netflix while researching for something "worthy", or journaling while feeling guilty for not studying. But that’s not real rest.

That’s just multitasking in a guilt costume.

And the irony? This “fake resting” leaves me more tired. More anxious. Less motivated the next day.

But I’m learning: the mental spiral doesn’t mean I’m weak. It just means I’ve spent years internalizing the wrong metric for success. And rest, when done right, is a radical form of self-trust.

Why This Reaction Makes Sense

This guilt around rest didn’t come out of nowhere. We were raised in a system that rewards output and punishes pause. From school to work to social media, we’re constantly told to “hustle harder,” to “stay hungry,” and to chase success like rest is the obstacle in the way.

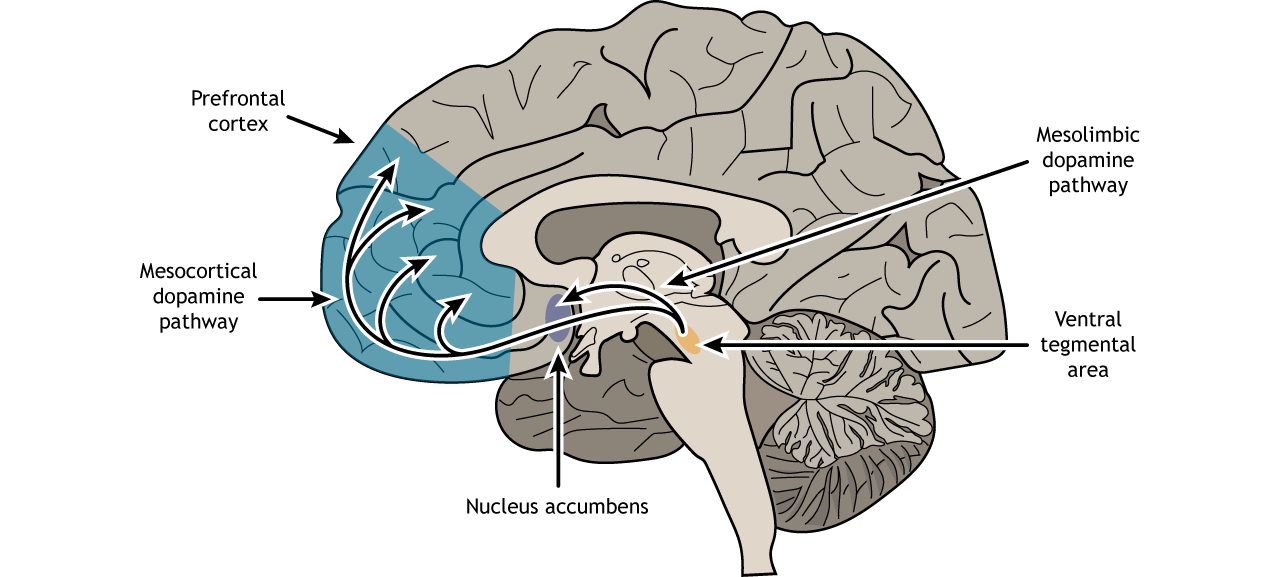

The dopamine reward system in our brain makes us crave the validation that comes from achievement (Watson, 2024). Every time we check off a task or accomplish something, we get a mini dopamine hit and over time, that can train us to associate productivity with self-worth.

Key Structures and Their Roles:

- Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA):

- Located in the midbrain, the VTA is the origin point for dopamine neurons that project to other parts of the brain (Hou et al., 2024). It’s often considered the “engine” of the reward system.

- Mesolimbic Dopamine Pathway:

- Projects from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens, a central player in the brain’s reward circuit.

- This pathway is heavily involved in pleasure, reinforcement learning, and addiction (Salamone & Correa, 2012). When you experience something rewarding (e.g., food, sex, social validation), dopamine is released here.

- Nucleus Accumbens:

- Acts as the “pleasure center” of the brain. Dopamine release in this region reinforces behaviors by making them feel satisfying or pleasurable (Xu et al., 2024).

- Mesocortical Dopamine Pathway:

- Projects from the VTA to the prefrontal cortex.

- This pathway is essential for attention, decision-making, planning, and self-control (Gorelova et al., 2011). It helps regulate goal-directed behavior and emotional responses.

- Prefrontal Cortex:

- The seat of higher-order cognition like judgment, impulse control, and rational thinking (Kim & Lee, 2011). When dopamine is properly regulated here, it supports motivation and long-term planning.

Meanwhile, chronic busyness can trigger sympathetic nervous system dominance (aka fight-or-flight mode) (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). If you’ve been living in this mode for a while, slowing down can feel wrong or even unsafe.

A 2021 study published in Psychological Science found that people often avoid leisure activities when they believe these activities make them appear lazy or unproductive to others.

So when you finally rest, your brain might actually interpret it as threatening like something’s wrong. That tight chest? That restlessness? That sudden urge to do something “useful”? It’s conditioning.

And honestly? You’re not lazy. You’re just healing from a world that confused burnout for bravery.

How I’m Reframing Rest

These days, I don’t try to force myself to love rest. I’m learning to meet it.

Instead of asking, “Did I do enough to deserve a break?”

I ask, “What would I say to a friend in this moment?”

Because if a friend told me they needed to slow down, I’d never say, “Well, have you earned it?”

Here’s what I’ve started doing slowly, inconsistently, but intentionally:

Naming the discomfort

When I feel guilty, I say it out loud: “This is the part where my brain thinks I should be doing more.” That awareness alone softens the guilt.

Replacing “lazy” with “processing.”

Rest isn’t wasted time. It’s the part where my brain and body get to digest everything else I’ve been doing.

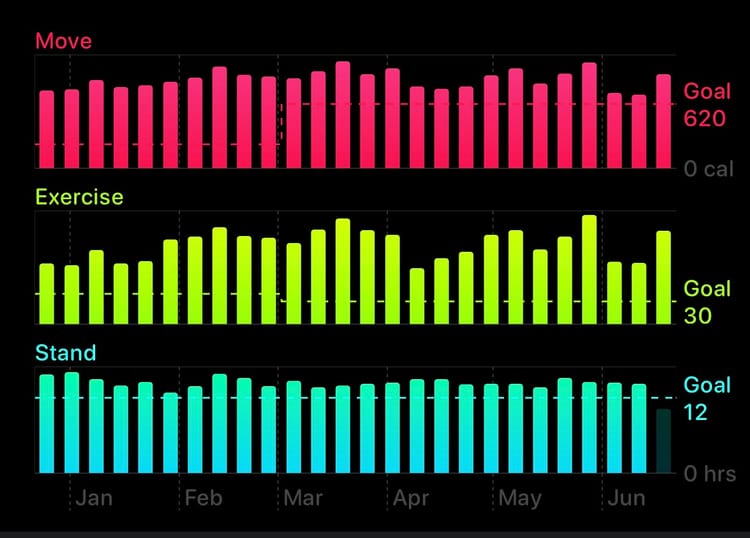

Scheduling rest with the same respect as work.

I block out chill time in my planner the same way I would a meeting or workout. Rest doesn’t need to be reactive. It can be proactive.

Not calling it “doing nothing.”

I call it recovery. Reset. Integration. Because that’s what it really is.

Most importantly, I’m learning that rest doesn’t need to look productive to be valid. It doesn’t need to be aesthetic. I don’t need to meditate for 30 minutes or read a wellness book.

Sometimes, rest is just lying in bed, hugging a pillow, staring at the ceiling, and breathing. And that’s still healing.

Things I Remind Myself On Rest Days

On days when doing nothing feels like failing, I repeat these truths like mantras:

- “Rest is not the opposite of productivity — it’s part of it.”

- “My body is wise. If it’s asking for rest, it’s not weakness. It’s communication.”

- “There’s no moral value in being busy.”

- “Rest is not something to earn, it’s something I deserve.”

- “Slow is still forward.”

These are quiet truths. But on the loud, guilty days, they matter more than ever.

Conclusion

In a world obsessed with grind culture, resting on purpose can feel radical. But it’s one of the most powerful acts of self-preservation we have.

We weren’t built to run like machines. Even nature has seasons. Even the strongest hearts take breaks between beats.

And maybe that’s what we need to remember:

The pause is part of the rhythm. It doesn’t mean you’ve stopped. It means you’re alive.

So if you’re reading this on your rest day, half-dressed in soft pajamas, scrolling instead of stretching, breathing instead of building, I see you.

You’re not lazy.

You’re healing.

And that counts.

References:

Cleveland Clinic. (2022, June 6). Sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23262-sympathetic-nervous-system-sns-fight-or-flight

Gorelova, N., Mulholland, P. J., Chandler, L. J., & Seamans, J. K. (2011). The Glutamatergic Component of the Mesocortical Pathway Emanating from Different Subregions of the Ventral Midbrain. Cerebral Cortex, 22(2), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhr107

Henley, C. (2021). Motivation and Reward. Openbooks.lib.msu.edu. https://openbooks.lib.msu.edu/neuroscience/chapter/motivation-and-reward/

Hou, G., Hao, M., Duan, J., & Han, M.-H. (2024). The Formation and Function of the VTA Dopamine System. International Journal of Molecular Sciences (Online), 25(7), 3875–3875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25073875

Huynh, A. (2022, May 3). Unlinking Your Self-Worth From Your Work. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/unlinking-your-self-worth-from-your-work-5222442

Kim, S., & Lee, D. (2011). Prefrontal Cortex and Impulsive Decision Making. Biological Psychiatry, 69(12), 1140–1146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.005

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Daley, C. E. (1999). Perfectionism and statistics anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 26(6), 1089–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00214-1

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2000_RyanDeci_SDT.pdf

Salamone, John D., & Correa, M. (2012). The Mysterious Motivational Functions of Mesolimbic Dopamine. Neuron, 76(3), 470–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.021

Watson, S. (2024, April 18). Dopamine: the Pathway to Pleasure. Harvard Health; Harvard Medical School. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/dopamine-the-pathway-to-pleasure

Xu, Y., Lin, Y., Yu, M., & Zhou, K. (2024). The nucleus accumbens in reward and aversion processing: insights and implications. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2024.1420028

Young, S. (2018, December 13). What is Productivity Guilt? (And How Can You Prevent It?). Scott H Young. https://www.scotthyoung.com/blog/2018/12/13/productivity-guilt/

Member discussion