The Science Behind Autodidactic Learning: Why Teaching Yourself Actually Works

Traditional learning isn’t always enough.

As a college student, I’ve had to teach myself a lot — way before the professor even uploads the lecture slides.

I’ve often found myself going down YouTube videos or breaking down journal articles or reputable blog websites just to keep up or get ahead.

At some point, I realized that I was teaching myself. And it was working.

That’s when I stumbled across the word autodidact, someone who learns independently, without formal instruction.

Turns out, there’s real science behind why self-learning works. From how the brain forms memory to how motivation impacts retention, this post is a deep dive into what makes self-taught learning so powerful and how anyone can become an effective autodidact.

What Is Autodidactic Learning?

Autodidacticism sounds intimidating, but it’s just a fancy term for something incredibly human: learning on your own.

Wikipedia defined autodidact as someone who takes their education into their own hands, whether through books, videos, podcasts, online courses, or even just life experience. Think of people like:

- Leonardo da Vinci, who dissected cadavers to learn anatomy without formal medical training.

- Maya Angelou, who credited much of her knowledge to libraries rather than school.

- Or even modern-day coders and creators who master skills through YouTube and Reddit threads.

Self-learning is an expansion. It’s realizing that learning doesn’t stop at the classroom door. In fact, in a world overflowing with free information, not being an autodidact might actually hold you back.

How the Brain Learns (A Crash Course)

Okay, mini neuroscience class incoming — but don’t worry, I made it as simple as possible.

Your brain is built to learn. At the core of that is a magical concept called neuroplasticity. This means your brain can literally rewire itself in response to learning and experience (Physiopedia, 2024). The more you challenge it, the stronger those neural connections become.

Here are a few key brain functions involved in learning:

Memory Formation

- When you learn something new, your brain first holds it in short-term memory (like RAM on a computer) (Sterling, 2017).

- If you review or use the info again, it moves into long-term memory, thanks to the hippocampus (Cleveland Clinic , 2024).

- This is why repetition and application matter so much. You’re reinforcing those pathways.

Dopamine and Reward

- Learning activates the brain’s dopamine system — especially when it feels rewarding (Lewis et al., 2021).

- When you’re genuinely curious about a topic (say, dragons or black holes), your brain releases dopamine that helps cement learning (Britannica, 2019).

- That’s why you remember random facts from YouTube videos more than some textbook chapters — your interest turns on the learning circuits.

Curiosity = Learning Power-Up

- A study from the University of California, Fell & Davis (2014) found that curiosity not only improves learning about the topic at hand but also boosts memory for unrelated information learned during that time.

- In short: if you’re curious, your brain becomes a sponge.

So, if you’ve ever taught yourself something because you wanted to, not because you had to — congrats. Your brain was fully activated, and you were learning in one of the most natural, effective ways possible.

You can watch this YouTube video to learn more:

Why Autodidacts Thrive: The Cognitive Science Behind It

So what makes self-taught learners so effective? Why do some people learn more outside of class than inside it?

It all boils down to how the brain is wired to engage with autonomy and how personalized learning taps into motivation, memory, and deeper understanding.

Autonomy Increases Motivation

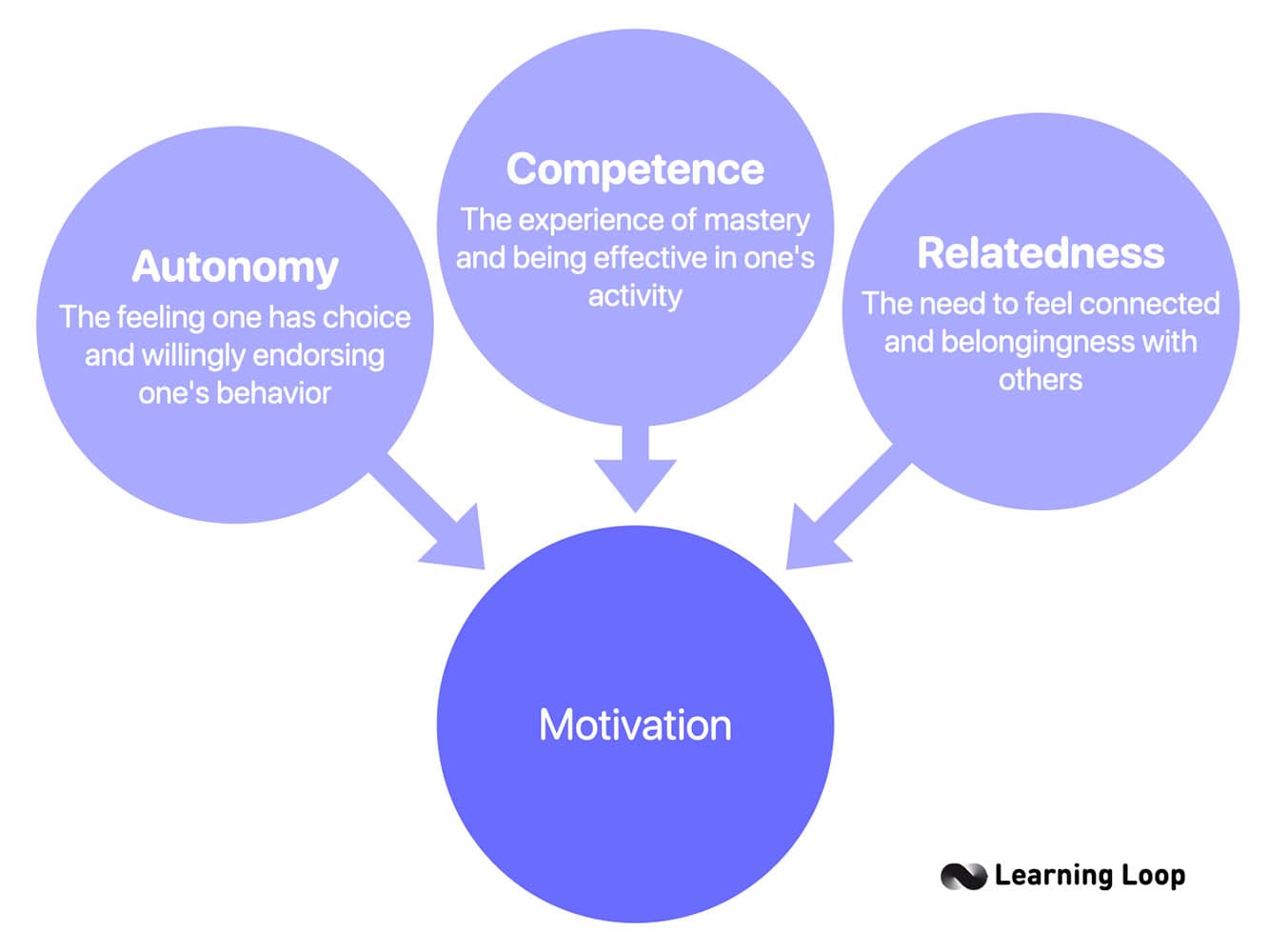

According to Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), humans have three basic psychological needs:

- Autonomy (control over what we do),

- Competence (feeling effective),

- Relatedness (feeling connected).

When you’re learning by choice not by syllabus, you’re fulfilling autonomy and competence, which spikes motivation and makes you want to keep going. This is good for long-term retention (Wang et al., 2019).

Deeper Learning Through Constructivism

Autodidacts unknowingly follow constructivist learning theory, which is the idea that we build knowledge through experience and context (ELM Learning, 2024).

When you teach yourself, you:

- Connect new info to what you already know,

- Organize ideas in ways that make sense to you,

- Apply learning immediately, often in real-world contexts (like coding, editing, or solving a real problem).

This is active learning, not passive memorization and it’s exactly what cognitive scientists say leads to long-term understanding.

Metacognition

Autodidacts constantly monitor their own understanding:

- “Do I really get this?”

- “How could I explain this better?”

- “Why does this method work?”

This is metacognition, or the ability to reflect on and regulate your own thought process (Sword, 2021). According to Stanton et al. (2021), it is one of the strongest predictors of academic success and autodidactic learners practice it naturally because no one else is guiding them.

Research and Studies That Back It Up

You don’t have to take my word for it because there’s actual science that supports the power of self-directed learning.

Study #1: Curiosity Enhances Learning

A 2014 study found that curiosity not only enhances learning about the subject you’re curious about but it also boosts memory for unrelated information learned around the same time (Stenger, 2014).

When you’re curious, your brain becomes more receptive, lighting up regions involved in reward and memory.

That’s why going down a Wikipedia rabbit hole sometimes teaches you more than a structured lecture ever could.

Study #2: Self-Directed Learning Strengthens Memory

A 2014 study by Markant et al. found that self-directed learning significantly improves recognition memory compared to passive observation, even under minimal conditions such as simply pressing a button to move to the next item.

The research showed that the benefit isn’t just from choosing what to study, but from controlling when to study it.

Why? Choice promotes deeper engagement and tailored learning paths, making the info more “sticky” in your brain.

Study #3: Active Learning Beats Passive Learning

A 2014 study published in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) showed that students in active learning environments perform significantly better than those in traditional lecture settings (Freeman, 2014).

And autodidactic learning, by nature, is active — you’re searching, summarizing, questioning, and applying, not just sitting back and listening.

The Tools That Empower Autodidacts Today (from Someone Doing It)

We’re in the best era in human history to teach ourselves anything. You no longer need an elite school or expensive degree to learn deeply — just Wi-Fi and a will to keep going.

Here are some of the tools that have personally helped me learn better, faster, and more enjoyably:

YouTube University

I’ve watched some lectures from Yale, MIT, and Stanford — for free.

Whether it’s neuroscience, history, or productivity breakdowns, YouTube has taught me more than some actual classes. (Shoutout to channels like CrashCourse, Ali Abdaal, and Kurzgesagt.)

Notion, Obsidian & Apple Notes

I used to organize all my self-study notes in Notion. For deeper, interconnected thinking, I used Obsidian. But now, I prefer simplicity and use Apple Notes.

Writing and connecting notes by hand (or keyboard) forces me to reflect, summarize, and make it mine not just highlight stuff I’ll forget in 10 minutes.

Podcasts and Audiobooks

While walking, working out, or doing chores — I learn.

Podcasts like Huberman Lab, Jay Shetty, or The Tim Ferriss Show constantly introduce new ideas or deepen old ones. It turns downtime into learning time.

Free Courses

- Coursera and edX – legit university courses

- Khan Academy – god-tier for math and science

- Duolingo – yep, even language learning counts

I once took a full course on the biology of aging just because I was curious about senescence. That’s the beauty of self-learning: no grades, just growth.

Common Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

Learning on your own is powerful — but it’s not perfect. Here are a few traps I’ve run into (and how I’ve learned to deal with them):

Information Overload

The internet is amazing — but it can drown you in tabs.

You watch one lecture, then open five more. Suddenly you’re watching a video on string theory when you just wanted to learn Excel.

Fix: I set learning goals per week. One topic, one direction. Everything else goes in a “Later” folder. Curiosity is great but focus is magic.

Shiny Object Syndrome

I used to jump from productivity tips to digital minimalism to stoicism to web development… and never stuck with any of them long enough to go deep.

Fix: I use the “5-Hour Rule” (coined by Benjamin Franklin): 1 hour a day, 5 days a week, focused on one area. That gives me space to dive deep before jumping into a new rabbit hole.

Lack of Structure

No deadlines. No tests. Just vibes. That’s the downside of freedom — it’s easy to get lost.

Fix: I give myself mini-assignments. Write a summary. Make a flashcard set. Explain it to someone. The act of producing something = proof that I learned it.

Isolation

Self-learning can be… well, self-ish. You don’t get peer discussion or feedback.

Fix: I’ve joined Discord communities, subreddits, and learning forums to ask questions, share progress, and realize I’m not alone.

Can Anyone Be an Autodidact?

Short answer? Yes — but with a twist.

Being an autodidact isn’t about being “naturally smart” or having some superhuman attention span. It’s about curiosity, consistency, and ownership. It’s about knowing that the world is huge, wild, and weird and choosing to engage with it on your own terms.

Some people will say, “I’m not disciplined enough.”

But autodidactic learning is about showing up, imperfectly, because something genuinely pulls you toward it.

Some days, that pull is strong.

Other days, it’s a whisper — and you have to lean in anyway.

Personally? I’m a 20-year-old college student who started reading studies on senescence for fun. Not because anyone told me to. Just because I had to know.

That’s the spark. That’s where it starts.

And the good news? You can light it anytime.

Conclusion

In a world where facts are everywhere but attention is rare, choosing to learn — deeply, deliberately, joyfully is a rebellious act.

Autodidacts don’t wait for the curriculum.

They build it.

They don’t chase grades.

They chase understanding.

And they don’t always know where the path will lead but they trust that walking it is worth it.

Optional Bonus Section: “My Self-Learning Bucket List”

Here’s a peek at topics I’ve taught myself (or want to):

- ✅ Basics of neuroscience & brain plasticity

- ✅ Mitochondrial health + aging research

- ✅ Beginner Python (for data stuff)

- 📚 Philosophy (especially stoicism and existentialism)

- 📚 Graphic designing

- 📚 Songwriting and music theory

- 📚 The evolution of language and grammar

- 📚 Filipino history beyond textbooks

- 📚 Understanding AI ethics & prompt engineering

You don’t need permission to learn.

You just need a starting point.

What’s on your list? :))

References:

Britannica. (2019). Britannica’s Curiosity Compass: the Science of Curiosity. Britannica’s Curiosity Compass. https://curiosity.britannica.com/science-of-curiosity.html

Cleveland Clinic . (2024, May 14). Hippocampus. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/hippocampus

ELM Learning. (2024). Constructivist Learning Theory. ELM Learning. https://elmlearning.com/hub/learning-theories/constructivism/

Fell, A., & Davis, U. (2014, October 2). Curiosity helps learning and memory. University of California. https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/curiosity-helps-learning-and-memory

Freeman, S. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Lewis, R. G., Florio, E., Punzo, D., & Borrelli, E. (2021). The Brain’s Reward System in Health and Disease. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1344(1344), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81147-1_4

Markant, D., DuBrow, S., Davachi, L., & Gureckis, T. M. (2014). Deconstructing the effect of self-directed study on episodic memory. Memory & Cognition, 42(8), 1211–1224. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-014-0435-9

Physiopedia. (2024). Neuroplasticity. Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Neuroplasticity

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2000_RyanDeci_SDT.pdf

Stanton, J. D., Sebesta, A. J., & Dunlosky, J. (2021). Fostering metacognition to support student learning and performance. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 20(2). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.20-12-0289

Stenger, M. (2014, December 17). Why Curiosity Enhances Learning. Edutopia; George Lucas Educational Foundation. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/why-curiosity-enhances-learning-marianne-stenger

Sterling, C. (2017, July 25). What Happens to Your Brain When You Learn a New Skill? - Office of Professional Education | Central Connecticut State University. Office of Professional Education | Central Connecticut State University. https://pe.ccsu.edu/what-happens-to-your-brain-when-you-learn-a-new-skill/

Sword, R. (2021, March 17). Metacognition | Teaching Strategies & Classroom Activities. The Hub | High Speed Training. https://www.highspeedtraining.co.uk/hub/metacognition-in-the-classroom/

Wang, C. K. John., Liu, W. C., Kee, Y. H., & Chian, L. K. (2019). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: understanding students’ motivational processes using the self-determination theory. Heliyon, 5(7), e01983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01983

Member discussion